Deux Jours, Une Nuit is a dreary and mundane French “art” film directed by Belgium’s Dardenne brothers. Marion Cotillard, whom American audiences may remember as the femme fatale Miranda in The Dark Knight Rises, stars as Sandra, a working mother whose poor psychological health has kept her at home and away from her job for some time. In her absence, her boss has given her coworkers an offer they find hard to refuse: either take Sandra back at their present wage rate, or agree to terminate her in exchange for a raise for everyone else. Due to irregularities in the circumstances of their initial decision, which has (unsurprisingly) gone against her, the workers are to be given a chance to hold a second vote. Sandra now has one weekend – the two days and one night of the title – to locate and approach each of her coworkers to convince them to take her back and forfeit the promised raise.

Nothing about Sandra, who suffers from depression and spends most of the movie moping, despairing, and gobbling Xanax tablets, is particularly interesting, and one suspects that this is intentional; she stands for the common person who is too often forgotten. Scenes of her intermittently breaking down and being encouraged by her sensitive husband (Fabrizio Rongione) to persevere and not to give up on her peers and their dormant capacity for selflessness are, unfortunately, somewhat repetitive, and not the strongest material to support an entire feature film. What ultimately saves and elevates Two Days, One Night above the level of tedium is the earnestness of the film’s key performances.

[WARNING: POTENTIAL SPOILERS]

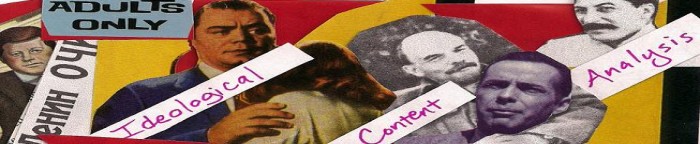

3.5 out of 5 stars. Ideological Content Analysis indicates that Two Days, One Night is:

6. Anti-American. The selfish Julien (Laurent Caron), a collaborationist co-conspirator with the workplace management, wears a “USA” patch on his shirt, perhaps signifying his sympathy with neoliberalism.

5. Anti-marriage. Sandra’s coworker Anne (Christelle Cornil) determines to leave her husband after years of being bullied.

4. Anti-drug. Sandra’s abuse of Xanax is worrying to her husband, whose concerns are shown to be warranted when she attempts suicide with an overdose.

3. Pro-union. The filmmakers, in an interview featured on the Criterion Blu-ray, say that their intent was to illustrate the “savagery” of companies whose workforces are not unionized. “We thought that with a nonunion company, we’d be closer to the raw truth of the social situation people experience today.”

2. Ostensibly anti-capitalistic, with workers pitted against each other by capital.

1. Dysgenic, pro-immigration, and crypto-corporate. Two Days, One Night is fundamentally disingenuous and misleading in framing the plight of the western worker as an individual rather than a national-racial dilemma. People are, of course, individuals on one level of their experience; but the inundation of European and European-descended peoples with Third World undesirables is precisely what has suppressed the typical worker’s wages and standard of living. In the end, when the tables are turned, and Sandra has the option of taking her job back on the stipulation that Alphonse (Serge Koto), an African, will be terminated, viewers are expected to be inspired that Sandra, playing the good goy, makes the wrong decision and sacrifices her own livelihood to save the congoid. Two Days, One Night goes out of its way to depict non-white immigrants as gentle, helpful souls and credits to their new communities, and even includes an African doctor (Tom Adjibi) who saves Sandra’s life after her overdose. To this extent, then, the film promotes a de facto corporate-state agenda.

Have shopping to do and want to support icareviews? The author receives a modest commission on Amazon purchases made through this link: http://amzn.to/1RVvbIU