Director Richard Schenkman, whose previous efforts range from Playboy documentaries to the abysmal Abraham Lincoln vs. Zombies, delivers a surprising winner with this tense home invasion shocker.

Mischief Night evokes immediate sympathy and concern for protagonist Emily (Noell Coet), a girl psychosomatically blinded after her mother died in a car accident. When Emily’s father (Daniel Hugh Kelly), with her encouragement, leaves her alone in the house on what happens to be her community’s annual Mischief Night – an occasion for spooky pranksterism – she finds herself at the mercy of a mysterious intruder (or is that intruders?) in a raincoat. The resulting film is a genuine tingler that raises the bar for blind girl terror, besting Wait Until Dark and Silent Night, Deadly Night III: Better Watch Out in terms of its sheer contagious fright.

The most frustrating aspect of Mischief Night is the muddiness of its moral universe – and, ultimately, its consequent meaninglessness. A fun but superfluous prologue that punishes two fornicators suggests that the Mischief Night killer or killers are disgruntled moralists or judgmental fire-and-brimstone vigilantes of the type represented in The Collection. Subsequent murders, however, lack this puritanical dimension, with victim selection failing to point to any unifying principle other than maximum terror. For most of the movie, the killers function as personifications or agents of a personal Hell for Emily, taking out of commission one by one the people and things that give her a sense of security – a theme that would have been strengthened if the screenwriters had excluded some of the extraneous deaths.

Flaws aside, Mischief Night is as scary as anything the viewer is likely to find at the Redbox, and is therefore happily recommended.

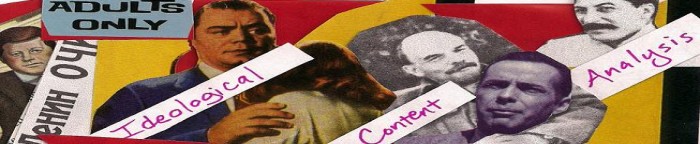

4.5 stars. Ideological Content Analysis indicates that Mischief Night is:

[WARNING: POTENTIAL SPOILERS]

7. Class-conscious. Wealth and a comfortable home afford no protection from reality or from the moral ramifications of sin.

6. Pro-castration. Emily’s father, somewhat reminiscent of Henry Winkler in wimpy Waterboy mode, is a model sensitive man.

5. Liberal. An old man (Richard Riehle) listening to a conservative talk radio program is dispatched almost as soon as he appears. This might be interpreted as an indication that the old conservative certainties of traditional values and Constitutional republicanism are dead or no longer a feasible defense of America; but more likely is that this is simply gratuitous spite directed at Limbaugh listeners.

4. Anti-slut. An adulteress (Erica Leerhsen) is terrorized during the opening sequence. Emily’s physical closeness with and trust of her boyfriend (Ian Bamberg) is a source of discomfort for the viewer.

3. Anti-gun. Emily’s father accidentally shoots her boyfriend, believing him to be an intruder.

2. Feminist. Emily’s disability has caused her to become highly self-reliant in ordinary circumstances. She proves more valiant than her father in the defense of their home and even asserts an imaginary phallus in the form of a chainsaw.

1. Pro-family. Emily is close with her father, and her disturbance after her mother’s death, a rupture of the family unit, has left her blind and, if not helpless, then at a significant disadvantage. The father, however, is rather girly and ineffectual, thus mitigating the movie’s pro-family credentials.

Looks like Trayvon!

Call Zimmerman!

The costume design for the killer is super-generic in Mischief Night. It’s sort of a composite of killers from other movies onto which you can project your own evil intentions or meaning. The atmosphere, fun factor, and structuring of the suspense sequences are the reasons to see this one. The villainy is strictly off-brand, though.

I’ll look for it on youtube.